I’m writing a novel in InDesign—that is, writing and arranging the layout at the same time. I’ve been researching the history of page layouts, not only in the current age of desktop publishing and its modernist precursors, but in various premodern and non-Western cultures. The idea is to repurpose complex layouts for use in contemporary experimental fiction. How, for example, can the rhetorical aims of medieval glosses be used for contemporary experimental fiction? How can InDesign and other current resources move the practice of the novel forward? Can multiple columns embody the postmodern interest in the divided self? Are nonfiction experiments like Derrida’s Glas related to the current concerns of fiction? Can it be useful to echo well-known page layouts like the Talmud or medieval commentaries in a contemporary text? Can marginal notes be an opportunity for the narrator to speak about their own text? How many voices can a page of fiction embody?

The posts are:

Marginal notes

Along the way I will offer critiques of formatted texts by Danielewski, Butor, Michaux, Schmidt, Fritz, Brooke-Rose, Derrida, Lebensztejn, and others. My interest here doesn’t include pages presented as images, as in concrete poetry and artists’ books, but rather pages where the formatting contributes to the meaning of the narrative. A formatted page, in this understanding, can be put into other fonts: what matters is the relation between the text elements—how they speak to each other and to the history of abnormally formatted texts.

The previous post was about notes that are partly in the margins and partly in the body text, so that they hollow out a space for themselves in the body text. This time the subject is notes that are only in the margins: real marginalia. Most of the scholarship, like H.J. Jackson’s Marginalia (2001) is on handwritten marginal notes, but I am concerned with typeset maginal notes because they are part of the book’s initial conception. This sort of marginal note is not paraliterary, in Genette’s term, but intrinsic to the text.

Marginal notes, printed or not, can be dangerous. They can take over their margins, threatening to become as interesting as the main text, as in this book on astronomy.1

Marginal notes in Arabic are called هامشيات ḥamishiyyat, and in Greek (borrowed into Latin) scholia. The Latinate word in English, marginalia, is post-classical, and properly speaking it pertains to an antiquarian, classicizing period in European publishing. The word glosses is borrowed from medieval practices, as in the first post in this series, which discusses glossae, commentaries on classical or Biblical texts. For my purposes a formal definition is enough: marginal notes occupy the margins, or more precisely, they create new margins, tighter ones. Left-justified marginal notes on the left side of the body text create very narrow margins between themselves and the edge of the page or the gutter.

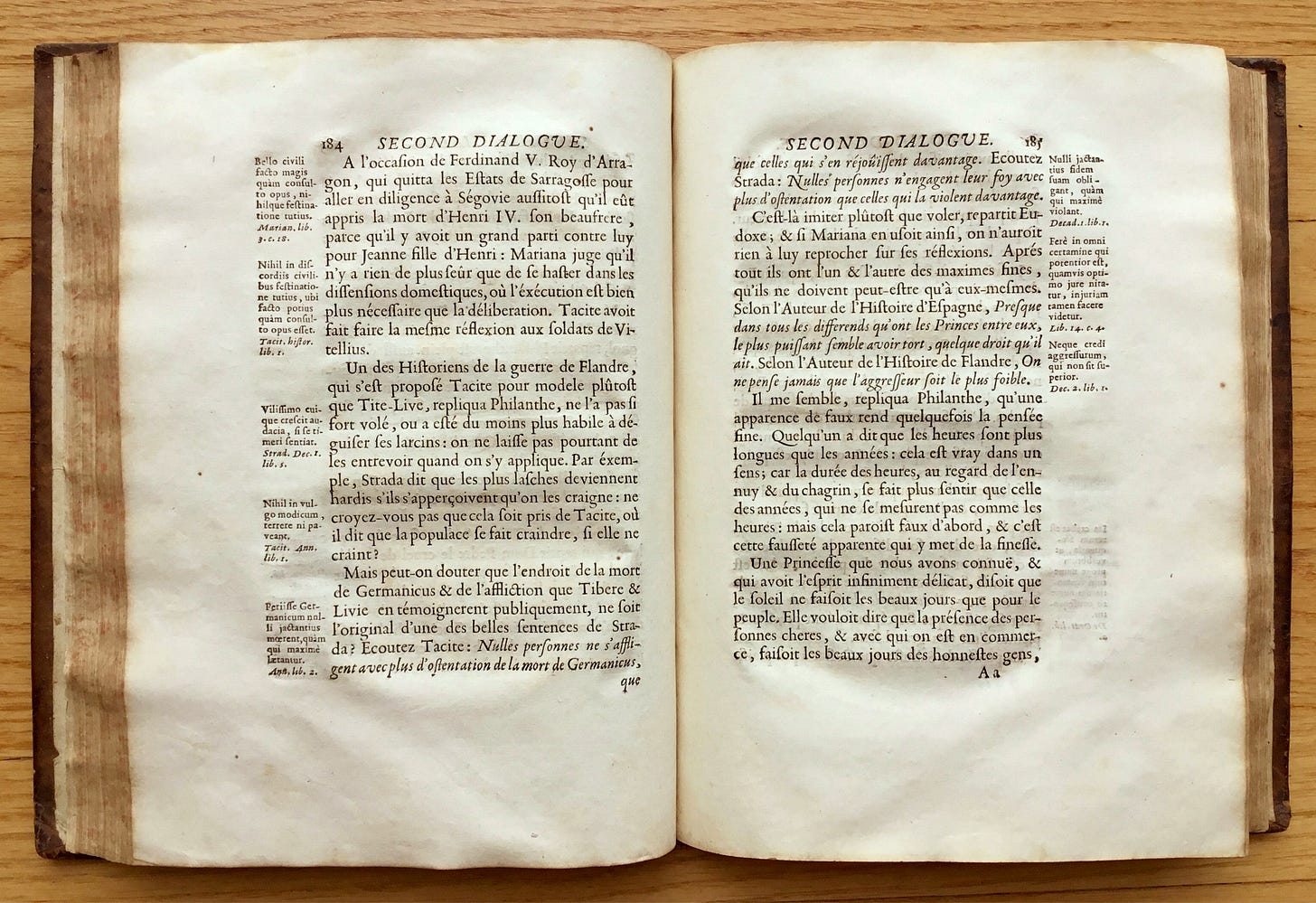

Nominally marginal notes simply explain the body text, but they also accompany, protect, and even confine the body text. Here is a typical example, from the Abbé Bouhours’s La Manière de bien penser dans les ouvrages d’esprit (1687), a book full of beautiful thoughts beautifully arranged. The marginal notes are Latin quotations from the authors who are mentioned in the dialogue, in this case Tacitus. Like all marginal notes, they do more than simply elucidate the main text. In Bouhours’s work they stabilize the free-ranging dialogue (Bouhours’s imagined conversations are one of the predecesors of Diderot’s), shoring it up with classical sources.

This is a later edition of another of Bouhours’s books, Pensées ingénieuses des anciens et des modernes (1758).

It’s a small 12° (duodecimo), and the scattered Latin glosses are suited to the impressionistic collection of thoughts and poems, in this case a passage in Pliny. The current custom of “pull quotes” (discussed in the second of these posts) is an atrophied descendant of marginal glosses like these, because pull quotes don’t add anything that’s not in the body text. They only attract the eye. Marginal notes like these add the crucial classicism Bouhours valued without interrupting the spoken French he practiced.

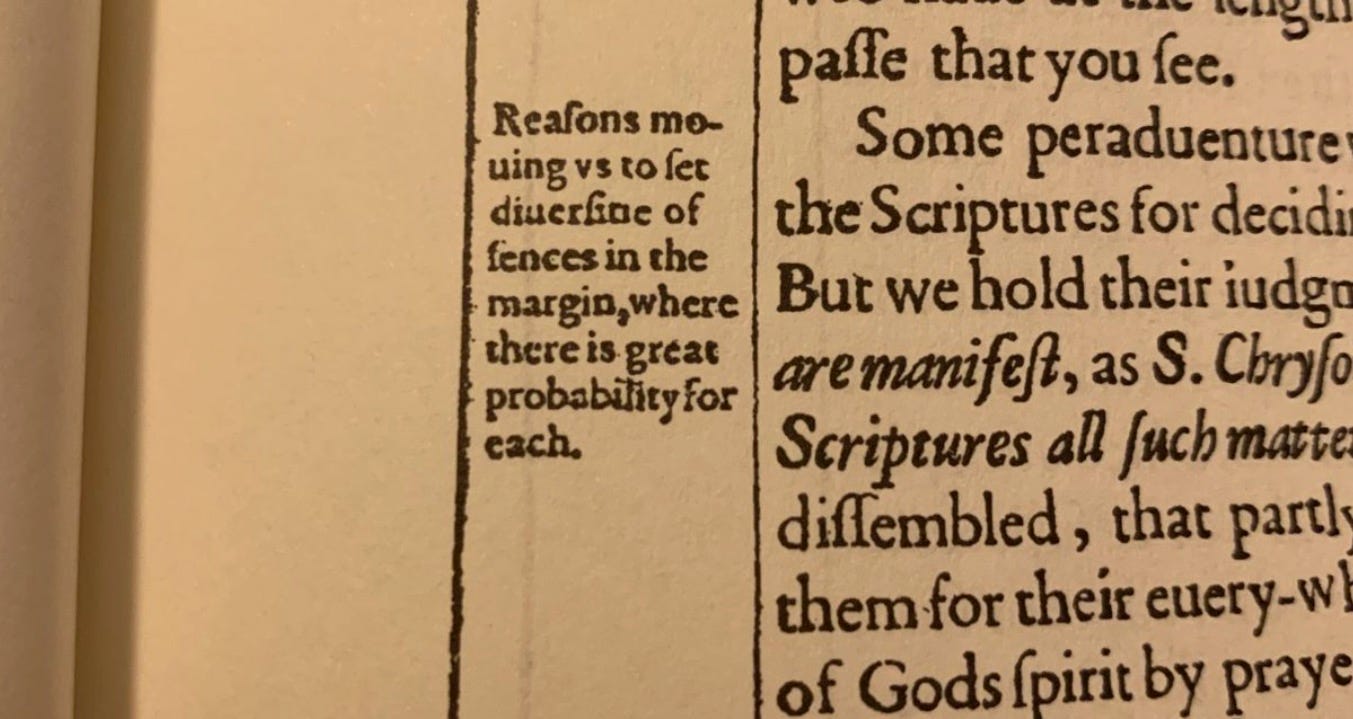

These examples are benign and harmonious with the author’s intentions, but like footnotes, marginal notes always also advocate and defend. They necessarily present the text as in some way deficient, and propose themselves as definitive. Often, as Evelyn Tribble has shown in Margins and Marignality (1993), marginal notes are aimed not so much at the body text as at other books: they can argue with the reader, and they often participate in intertextual controversies. In the Reformation, for example, glosses in Catholic Bibles armed readers to refute Protestants, and vice versa.

The Douay-Rheims Bible (1582/1635) shows the Biblical text on the left, with verse numbers in the inner margin as in contemporary Bibles and left-justified commentary on the outside margin. On the right page are annotations in a smaller font (endnotes to the chapter in Genesis), with more commentary on the outside margin and italic cross-references in abbreviated form on the inner magin.

It’s typical that commentary on the outer margins has more room, and here it is intended to help Catholics in England argue against Protestants.

Tribble notes that Gayatri Spivak learned of this function of marginal notes sometime before 1989, and noted in an interview that she was “beginning to think of the concept-metaphor of margins more and more in terms of the history of margins: the place for the argument.. the place of interest for assertions rather than a shifting of the center” (p. 103). Bouhours’s classicizing notes are benign, but all marginal notes take positions in defense of a certain idea of the text that is implicitly inadequate or missing, whether they shore up the author’s authority, speak intertextually to other books (as in the Reformation debates), or address the reader’s implicit lack of understanding. They turn a coherent text into one that needs help, that is insufficiently eloquent or even damaged (as in glosses on classical texts like Sappho), dividing the text’s voice into an existing narrative and a voice that doubts, strengthens, or corrects.

There are interesting possibilities here for fiction. The outer margins (the ones that traditionally have more room) could be used for apostrophes aimed directly at readers, perhaps trying to persuade them of some particular interpretation of the main text. They would be outward-facing and metaleptic, rather than inward-facing and supportive.2 The narrator could speak in the margins, commenting on a text in which they are mentioned or in which they are the principal narrator, perhaps from a distance of experience or years.3 A page in a work of fiction that has marginal notes becomes a written document, even if the main text is a mimetic representation of events. That can be an interesting resource: it can bring the reader out of an immersion in the text and into an engagement with the act of writing (When did the narrator compose the book, exactly? When did they annotate it?). In that sense, marginal notes in fiction can be strategy for bringing the narrator closer to the writer, or the writer closer to the author—or conversely, for dividing the narrator into the person who experienced the events and the one who later ponders them.

In terms of typography, marginal notes that are left-justified on the outside margin persisted into the 20th century, I think mainly in French texts. They occur in Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, where sparse marginal references balance the personal nature of the book, giving it a more scholarly feel.

Left-justified marginal notes also occur in legal texts, like Edwardo Coke’s Commentary Upon Littleton (I have volumes from 1794), where legal citations on the outside margin serve the same cross-referencing purpose as the Biblical references on the inside margins of the Douay-Rheims Bible:

At the end of the previous post I was wondering what might happen if the body text gets squeezed out by the commentary. Here is a verso from an exceptionally complex Bible at the Bodeleian (thanks to Milovan Novakovic for pointing it out to me). The Biblical text, from Ecclesiasticus, is on the upper right. This is a verso page, and the full spread would show the passages from Ecclesiasticus in the middle, crowded not only by dishevelled ranks and files of columnar commentary and infestations of interlinear commentary, but also swarms of marginal notes.

It’s more an imperiled text than one protected and validated by commentary.

Among modern texts Meena Kandasamy’s Exquisite Cadavers is an extreme case, where the margin is given a third of the page. It’s nearly a double-column page, except that the formatting signals the left comments on the right, and not vice versa. This lack of ambiguity suits Kandaswamy’s purpose of asserting her work as fiction, in response to some reviews of her previous book, which had been understood as a memoir (Holly Williams in The Observer, October 1, 2019). In terms of authorial force, the two columns compete, fiction against political reality.

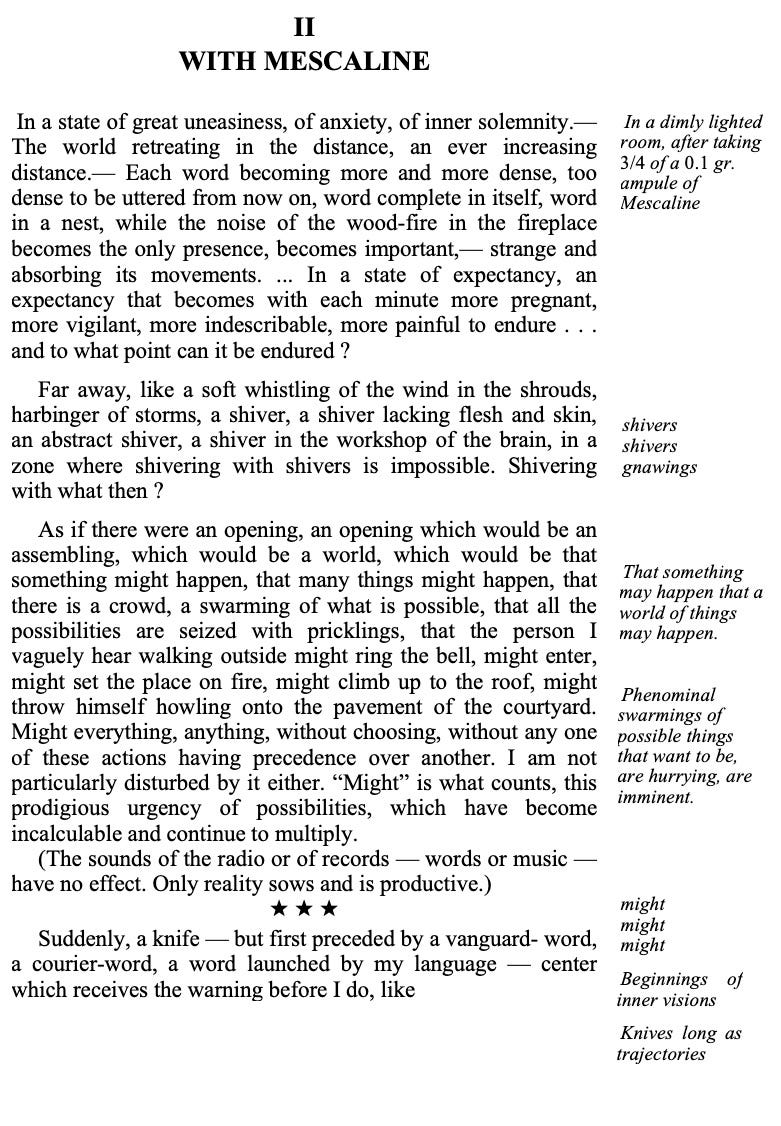

Another non-normative case is Henri Michaux’s mescaline diary, translated as Miserable Miracle. The italicized marginal notes were apparently written at the time. The justified text is a narrative explanation after the fact—or so it seems at first.

As the book goes on, the marginal notes become too sparse to be memory prompts. One page has only “distancing of a thought,” and, lower down, “echo.” The record of his “interrupted sentences, with syllables, flying off, [and] frayed” (p. 5) effectively stops, and the main text continues as the only record and commentary. It’s an interesting example of a struggle for voice and memory between body text and marginal notes.

In my own project I’m debating using marginal notes, just because they are so strongly metaleptic: who is speaking in the margins? The author? The main character, who is narrated in the fiction but is also the person who wrote the book? Does the voice in the marginal notes doubt everthing in the main text, paragraph by paragraph? Can that be sustained?

The best use of marginal notes that I know in postmodern fiction is Arno Schmidt’s Bottom’s Dream, and most of those are thought by the main character, not spoken—but that’s for a later post.

This is still an open question for me. I’d like to hear about other uses of marginal notes in modern and contemporary fiction, and of course unusual uses of printed marginal notes in premodern nonfiction.

There is also a literature on how to scan and typeset this sort of text. You can find some examples on Academia; but it’s not my main interest here.

In the Douay-Rheims Bible, the Bible chapters are followed by annotations: those, too, have potential for fiction. Say the principal fictional narrative is on the left page. Then the right would be commentary, perhaps another voice. I will explore this possibility in the fourth post, because these are essentially endnotes.

If the comments in the margin are continuous, then they would be like a page divided into columns, subject of another post. Marginal comments of the kinds I’m considering here are independent pararaphs, tied to passages in the body text.