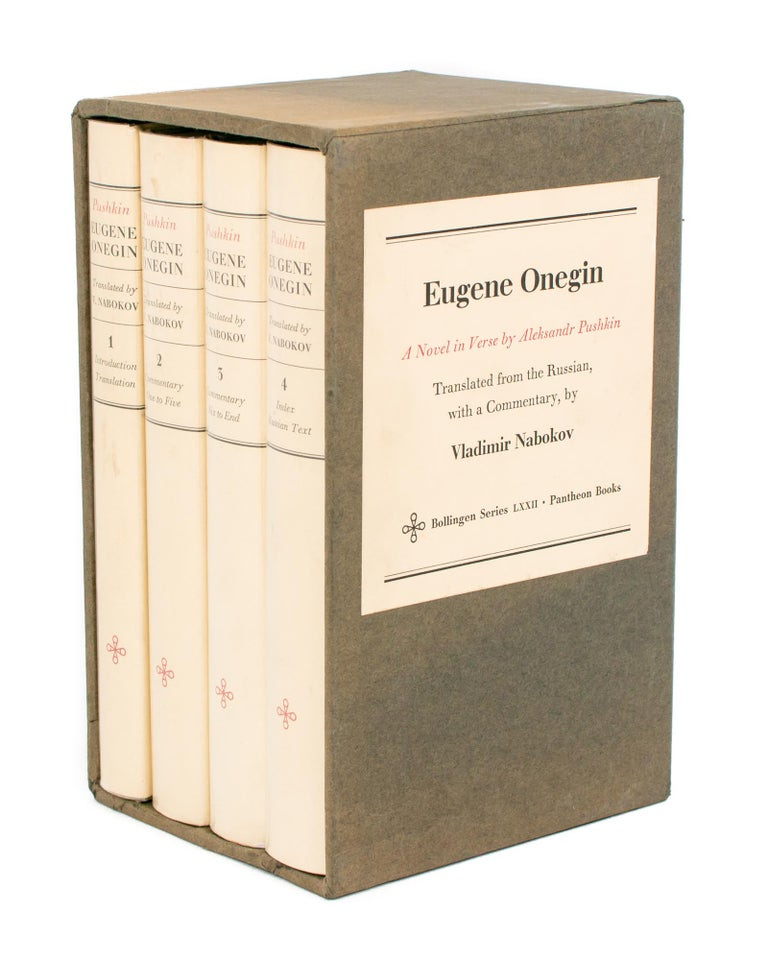

In 2016 I became one of just a few people, I think, who have read all four volumes of Nabokov’s translation and notes on Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. Nabokov’s edition has been notorious from the moment it appeared in 1964, both because it provides 1,200 pages of commentary for a slim 220 page verse novel, and because he insists on translating with literal fidelity, even when the results are awkward, archaic, or otherwise arguably unpoetic.

I read the four volumes as attentively as possible given that I don’t know Russian. That means I didn’t read the Russian facsimile of Pushkin’s poem that is reproduced in vol. 4, and I skipped the few untranslated transliterations. But I read the glosses on alliteration, Nabokov’s systems of transliteration, his 80-page study of Pushkin’s Abyssinian ancestor, and even the quixotic 100-page “Notes on Prosody.”

I did all this because I am interested in what can be done with footnotes in modern and contemporary scholarship and fiction. The footnotes in Pale Fire, written at the same time as Eugene Onegin, are simpler in terms of complexity of reference, but trickier in terms of voice. I will be posting separately on Pale Fire. There are also footnotes in Nabokov’s entomological publications, which have been collected and reprinted. But the notes in those texts can’t compare with the outlandishly and apparently endlessly compulsive footnotes in his four-volume edition of Eugene Onegin. I learned a lot from them, and eventually adopted some of Nabokov’s ideas in my own novel, which is coming out in five volumes, each with a different kind of footnote.1

That’s background, and I will be posting on footnotes separately, as an installment in this series on experimental page formats in fiction. This post considers several other issues raised by Nabokov’s project, and I’ll draw a general conclusion with the help of Edmund Wilson’s famously irritated review.2 And a final prefatory note: I’m also staying away from the translation debate.3 There’s a lot to be said about this aside from Nabokov’s attempt at literal translation.

1. Is the book boring?

It’s interesting to contemplate what counted as boring for a person willing to spend thousands of hours in libraries and in correspondence (this was well before the internet), assembling 1,200 pages of footnotes. At one point he says “the boredom of reading through the English, German, Polish, etc., translations... was too great even to be contemplated” (vol. 2, p. 102), but he did read the other translations, and he often compares them to his own.

Did he think of his activity as perverse? Possibly, at times. For example, he compiles every mention of the river that runs through Onegin’s estate; it occupies four pages. At the end he notes that Pushkin “took a perverse pleasure, it would seem, in finding various elegant Russian versions” of the ‘eaux-et-forets’ cliché"‘ (vol. 2, p. 203). A line later we’re told “it would be pedantic to list the innumerable examples of this ‘shady wood-murmuring brook’ symbiosis in western European poetry.” Fair enough, but also unbelievable enough, after four pages inventorying Pushkin’s brook, followed by the insinuation that Pushkin was “perverse.” There are a number of other such lists in the commentary; they are seldom dry and therefore boring in the ordinary sense, though of course some are, like the bare list of allusions to winter (vol. 2, p. 473). Overall there are remarkably few typically bibliophilic indulgences, like his complaint that a catalog of arms, issued by the Bulletin of the Public Museums of Milwaukee in 1928, misspells the name of a pistol manufacturer (vol. 3, p. 39).

Edmund Wilson thinks Nabokov’s Eugene Onegin shows “the Nabokov who bores and fatigues by overaccumulation,” which “contrasts with the authentic Nabokov and with the poet he is trying to illuminate.” But are they so different? And is “boring” the right word here? (“Fatiguing,” maybe. Leavened by perversity.) Nabokov also warns himself against becoming “didactic” like some commentators, and he praises those who attend to “professional matters” (vol. 1, p. 48).

Each of these meliorating terms could benefit from closer reading. Boredom, adequacy, didacticism, fatigue, and professionalism are all potentially intriguing. I found the 1,200 pages as interesting and energizing, in their different way, as 1,200 pages of Pale Fire, Lolita, Pnin, and whatever other books would have to be strapped together to comprise an equivalent bulk.

2. Precision

There’s also the trademark precision of his observation, on sharpest disaplay when it comes to flashing lights. Of the “rainbows” cast on snow by the light of horsedrawn coaches (One : XXVII : 9, in Nabokov's numbering of Eugene Onegin) he remarks:

My own fifty-year-old remembrance is not so much of prismatic colors cast upon snowdrifts by the two lateral lanterns of a brougham as of iridescent spicules around blurry street lights coming through its frost-foliated windows and breaking along the rim of the glass. [vol. 2, p. 110]

He is correcting Pushkin: the rainbows don’t form on the snow, you see them through the coaches’ windows; and they aren’t rainbows, they’re “spicules”; and note, Pushkin, that they break up along the rims of the glass—a detail you might have done well to remember, and which would have prompted you to be a bit more accurate.

3. Historiography

Scattered in these 1,200 pages is a wonderful essay on romanticism and neoclassicism, worthy of Arthur Lovejoy. Nabokov is good on passions (vol. 2, p. 256), and the “achromatic detail” of eighteenth-century nature poetry (vol. 2, p. 286), and there is a self-contained essay on the eleven (!) kinds of romanticism Pushkin would have recognized (vol. 3, pp. 32-37).

4. Criticism

Reviewers have noted Nabokov tends to give his opinions about sources, even if they’re not important or well-known authors, and even if Pushkin’s opinion of them may have been quite different. “There are readers,” he says, “who prefer Pushkin’s Scene from Faust (1825) to the whole of Goethe’s Faust, in which they distinguish a queer strain of triviality impairing the pounding of its profundities” (vol. 2, pp. 235-36). Rousseau’s Julie; or, The New Heloise was “total trash,” and his mind was “morbid, intricate, and at the same time rather naïve” (vol. 2, pp. 339-40). Virgil was “overrated,” and his Eclogues are “stale imitations of the idyls of Theocritus” (vol. 2, p. 322). (It’s always a pleasure to agree with Nabokov, just as it’s a surprise to be so politely but abruptly schooled.) He prefers Leibniz to Voltaire (vol. 3, p. 30), and he often calls Chateaubriand a writer “of genius”; he also likes Senancour, and seems consistently irritated by Rousseau.

Not all these are one liners. There is for example a trenchant, even poignant, two-page long assessment of the poet Evgeniy Baratinski. Nabokov thinks he is a case of a poet suspended between minor and major.

His elegies are keyed to the precise point where the languor of the heart and the pang of thought meet in a would-be burst of music; but a remote door seems to shut quietly, the poem ceases to vibrate (though its words may still linger) at the precise moment that we are about to surrender to it. [vol. 2, p. 380]

There’s also a wonderful three-page biography of a critic named Vilgelm Kuechelbeker (vol. 2, pp. 445-48).

It’s fascinating how little Nabokov praises Eugene Onegin: maybe a half-dozen times, but certainly less than the number of times he criticizes passages and entire chapters. Part of the reason is that what Nabokov treasures most is exactly what he cannot ever explain satisfactorily: “the only Russian element of importance” is “Pushkin’s language, undulating and flashing through verse melodies the likes of which had never been known before” (vol. 1, pp. 7-8). This passage is the crucial ending of his brief “Description of the Text,” and it closes with the motto: “there is no delight without the detail”: that’s 1,200 pages of delight here, but none is total, because little is in Russian.

As Wilson says in his review, Nabokov expends a lot of energy thinking about how Pushkin composed his novel in verse; Nabokov often mentions evidence that Pushkin hadn’t made up his mind, at a given point, where he might go. In all this, Nabokov’s concern is the accomplishment of the whole novel, which has coherence, unity, and symmetry: it’s not modern or even romantic way of judging art, so much as a classical one, and it’s culturally anomalous when it’s set alongside the knowing scholarly apparatus and the neighboring ironies of Pale Fire. Judging by classical coherence is of a piece with Nabokov’s admiration for the way Pushkin puts himself into the poem, along with some of his real-life friends (he even has his actual friends entertain his fictional ones), all without breaking the poem’s fabric. But none of this is my subject here. (See, for example, vol. 1, pp. 15-16, 19; and for an “admission,” p. 44.)

A last note on criticism: there are just a few subtle and evanescent moments in which Nabokov acknowledges, implies, or can be read as admitting, that Pushkin is the greater artist. One of the most curious, because it’s indirect, is the notes on the crucial scene in which Onegin kills Lenski in a duel. The first image we get of Lenski falling compares him to a snowball rolling down a slope. Nabokov patiently shows this is a cliché, not invented by Pushkin (vol. 3, p. 52). But then he goes on to say that the list of metaphors that follows (Six : XXXI : 10-14) is an intentional parody of Lenski’s poetic style: this seems improbable, simply because it would be distracting if readers were to think of it. But it makes perverse sense as Nabokov’s sincere attempt to defend his poet against more, and worse, clichés. And then—as if that wasn’t enough—Nabokov claims Pushkin’s final description of Lenski dead, as an empty house (One: XXII : 9) is showing off against Lenski’s poetry! I’d like to read these two pages of commentary in a Bloomian way, as the agon of one writer against another, except that I think Nabokov probably experienced these pages as the most sincere flattery of a superior artist.

5. Vocabulary

Of course his vocabulary is outlandish. Leave it to Nabokov to find an expression for the gesture of swinging one's arms in front, clapping, and then swinging them in back: “to beat goose” (vol. 2, p. 96). Or to tell us that “a rusalka is a female water sprite, a water nymph, a hydriad, a riparian mermaid, and, in the strict sense, differs from the maritime mermaid in having legs” (vol. 2, p. 246). Not only do we get a disquisition on the difference between Russian blini and American pancakes, we’re also told exactly how Russians ate their blini, including the number of bites per sitting (“as many as forty,” vol. 2 p. 299).

Because Pushkin attributes a mild form of foot fetishism to Onegin, Nabokov spends pages schooling us in women’s feet.

The associative sense of the Russian nozhki (conjuring a pair of small, elegant, high-instepped, slender-ankled lady’s feet) is a shade tenderer than the French petits poids; it has not the stodginess of the English “foot,” large or small, or the mawkishness of the German Fuesschen. [vol. 2, p. 115]

He counts the feet, even in the different translations, and jokes that one translator, who counts six feet in one passage, is “entomologically minded” (vol. 2, p. 116).

Wilson’s review is especially harsh on Nabokov’s choice of extremely obscure words. At times, Nabokov anticipates and defends himself in the notes; mainly he says he prefers exactitude to easy reading. But in the notes, where he’s not translating, the same Nabaokovian excesses recur. I stopped several times, for instance, over the notion of a “cataptromantic stanza” (vol. 2, p. 499). But I appreciate precision, and I don’t think it got in the way of the poetry; Nbokov has given me a strong sense of Pushkin, the kind that can’t be obtained if you don’t know what counts, for the translator, as precision.

6. Wilson’s review

The famous review appeared in the New York Review of Books, July 15, 1965. It is as clever as Gore Vidal in its insincere self-deprecation, mingled with genuine friendship. And it is fearless: Wilson corrects Nabokov on his knowledge of his own language. The review has been conflated with the later discussion about Nabokov’s extreme literalism in translation, but that’s not its argument. Midway through, Wilson makes a single devastating point: he says Nabokov didn’t understand the character Onegin:

Mr. Nabokov’s most serious failure, however—to try to get all my negatives out of the way—is one of interpretation. He has missed a fundamental point in the central situation. He finds himself unable to account for Evgeni Onegin’s behavior in first giving offense to Lensky by flirting with Olga at the ball and then, when Lensky challenges him to a duel, instead of managing a reconciliation, not merely accepting the challenge, but deliberately shooting first and to kill. Nabokov says that the latter act is “quite out of character.” He does not seem to be aware that Onegin, among his other qualities, is, in his translator’s favorite one syllable adjective, decidedly злой—that is, nasty, méchant.

I think this is right, and it is a masterstroke to place it in the middle of a generally quibbly review. Because I had never read Eugene Onegin before, I was an ideal reader of this passage; when I read the review, I had just finished Nabokov’s four volumes, and suddenly several dozen of his comments fell into place. He just couldn’t see that part of Onegin’s character. Here is an example, from many, of the kind of gloss that shows this lack. Nabokov is commenting on the word “inconsistencies” (One : LX : 6), noting Pushkin closes his first chapter by acknowledging “inconsistencies” in Onegin's character. Nabokov:

Hardly an allusion to chronological flaws; perhaps a reference to Onegin's dual nature--dry and romantic, chilly and ardent, superficial and penetrating. [vol. 2, p. 2154]

This just isn’t quite enough, and Wilson's comment throws it into strong relief. Sadly, Nabokov’s reply, and Wilson’s reply to him, are uncharacteristic, petty, and uninteresting.5 The two squabbled throughout their friendship, and there is a catty passage in the commentary in which Nabokov reproduces a translation of Wilson’s, which he says is “good,” but interlards it with italicized words, which he calls “a few minor inexactitudes” (vol. 2, p. 474).

7. Exile

It’s not the squabbling that makes Wilson’s review so excellent, it’s the balance between scrapping and large-scale assessments, not least his verdict that Nabokov’s Eugene Onegin is of a piece with everything else of Nabokov’s after his exile. It expresses “the situation, comic and pathetic, full of embarrassment and misunderstanding of the exile who cannot return, and one aspect of this is the case of the man who, like Nabokov, is torn between the culture he has left behind and that to which he is trying to adapt himself.” Nabokov sees Pushkin from a distance, and that must be especially painful. It drives—this is the implication—extreme performances of compulsive research. In that way even 1,200 pages of commentary, in all its microscopic kaleidoscopic telescopic excess, is not enough to convey the pathos of perpetual dislocation.

My own novel, Five Strange Languages, is in 5 volumes and has several kinds of footnotes. It’s being published by Unnamed Press in LA. In one of the published volumes, a character named Anneliese becomes fascinated by long, complex books, and she reads and reviews a number of them. That was therapeutic, as they say: I was lost in an apparently endless project, which I thought I’d never finish or even keep control of, and Anneliese gave voice to my anxiety. The next volume in the project will appear in 2026, and it has even more complex sorts of footnotes, endnotes, and marginal notes. Throughout, Nabokov has been a fruitful model.

An aside, on Ithaca. Nabokov wrote this largely, I think, in Ithaca, which is my home town, and he wrote it right around the year I was born, living in several houses near my parents’ house. The notes are full of remarks on America and American students. At one point he explains the differences between steaks: “The European beefsteak,” he writes, “used to be a small, thick, dark, ruddy, juicy, soft, special cut of tenderloin steak, with a generous edge of amber fat on the knife-side. It had little, if anything, in common with our American ‘steaks’—the tasteless meat of restless cattle” (vol. 2, p. 149). In another passage he introduces six entire pages dedicated to the analysis of two kinds of trees with the observation that his class of American students couldn’t identify an elm tree outside their window (vol. 3, p. 9). When I was growing up, elms hadn’t been decimated by the Dutch elm disease, and the ones outside the hall in which Nabokov taught had the characteristic long branches reaching to the lawn, as typically mid-century American a sight as it’s possible to imagine.

There is one mention of Talcotville, where Wilson lived (vol. 2, p. 391), and one mention of Ithaca, in an especially meaningful place, at the end of his commentary and before his long addenda. He quotes a Pushkin poem called “The Work” as an epigraph and epitaph for his commentary; in the poem, Pushkin says he’s finished with an exhausting work “of long years.” Nabokov writes the following in a footnote asterisked to the poem’s title: “Pushkin dated this poem: ‘Bolodino, Sept. 25, 1830, 3:15.’ Translated one hundred and twenty-six years later, in Ithaca, New York.” I was one year old at the time.

For this see Renate Lachmann and Mark Pettus, “Alexander Pushkin’s Novel in Verse, ‘Eugene Onegin,’ and Its Legacy in the Work of Vladimir Nabokov,” Pushkin Review / Пушкинский вестник 14 (2011): 1–33; Clarence Brown, “Nabokov’s Pushkin and Nabokov’s Nabokov,” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature 8 no. 2 (1967): 280–93; J. Clayton, “The Theory and Practice of Poetic Translation in Pushkin and Nabokov,” Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes 25 no. 1 (1983): 90–100; J. Thomas Shaw, “Translations of Onegin,” The Russian Review 24 no. 2 (1965): 111–27, all on JSTOR.

For other misunderstandings see vol. 3, p. 16, vol. 3, p. 62, and also vol. 3, p. 40.

New York Review of Books, August 26, 1965.

Great read, thank you for this

This was so enjoyable and intriguing. You have a soothing writing style, and I'm looking forward to your book!