Writers who won't tell us what's in their characters' minds, No. 5: Toward a theory of flat affect and lack of emotion

How to write characters who "prefer not" to say what's in their minds

This is a series of posts on a fascinating problem for contemporary fiction: What happens to fiction when a character’s mind is partly closed, either to the character or to the implied author? It’s not a problem to write about a character from the outside—to watch them, as we all watch one another, without having access to their mind. But it is a very difficult and interesting problem to “focalize” a character, in Gérard Genette’s term, so that we can read some of their thoughts, and yet to refuse others—to keep them off the page, or out of the character’s mind. To adopt and generalize Bartleby’s expression, what are the expressive possibilities of preferring not to say?

Here’s the series:

I’ve been thinking out loud, as it were, and all these posts are open to comments. I’d love to hear about other examples and theories.

As

reminded me, Camus’s The Stranger (1942) is a prototype of flat affect. Camus shows us again and again that Mearsault lacks conventional emotion and is indifferent to moral codes. From the outset the first-person narration creates the expectation of introspection:Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas. J’ai reçu un télégramme de l’asile : «Mère décédée. Enterrement demain. Sentiments distingués.» Cela ne veut rien dire. C’était peutêtre hier.

He never understands why he kills a man, and almost fails to see why he should try to understand. At the end of Part One, Mearsault allows himself some words of explanation, which Gérard Genette calls “the knee-jerk example for psychologically-oriented Camus Critics.” There are few such lapses, if that’s the right word for inexplicably intermittent moments of partial self-awareness.1

Other characters with flat affect relish their callousness, like Patrick Bateman in Ellis’s American Psycho. There’s usally the assumption, or the claim, that something made these people the way they are: parents, society, or—in the case of Camus—a meaningless universe that appears to encourage meaningless lives.

I would like to imagine this differently. What if the depiction of an absence of engagement, emotion, or reflection is itself the interesting project, and explanations are unnecessary? What if the lack of psychological depth does not point continuously to the novel’s perennial project of psychological portraiture? In that case writing about characters with flat affect and limited inner life would not be a social project, whose aim is to help us understand challenging people, or to think about how our world continues to produce them. It also wouldn’t be a philosophic project, designed to persuade readers that we all need to face existential loneliness, or to help readers feel better about lonely lives by telling them the entire universe is a vacuum of meaning. Something else would be the point, as it is in Bresson’s films when people spend so much screen time looking at their shoes.

This isn’t an easy topic, because writers have had different reasons for depicting characters with flat affect. Some are like unsmiling James Bond villains who know perfectly well what they are doing, and others are like Javier Bardem in No Country for Old Men, who experiences the world as a narrow game of violence. Some unemotional, affectless characters are intrinsically limited, like HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Others can be read as having unexpected depths, like Chauncey Gardiner or Forrest Gump.

I’m going to spend most of this essay arguing that all the explanations for such characters are misguided, distracting, premature, and unnecessary. Some people are emotionless. Some have limited or untracable inner lives. Different configurations of missing depth are all around us without the need to pretend they come from misconfigured societies or abusive families.

Beyond the explanatory narrartives, then, is a fascinating writing problem, and a challenge both for the novel and for theories about it. We do have access to Mearsault’s mind in the passages that have thrown lifelines to readers who need Mearsault to have thoughts of his own. Mearsault is uncomfortable trying to determine how to respond in certain situations where he knows something’s expected of him: that’s clearly a sort of rudimentary inner life. But his actions are so difficult to understand—most famously, he says he killed a man because the sun got in his eyes, and never seems to understand that there might be more to think about there—that it seems Camus must have hidden some parts of his mind from us. That’s a hard trick to pull off. How, as a writer, do you signal that you’re going to tell us some things, but not others, about your character’s thoughts? The challenge becomes nearly intractable when a reader begins to worry about the author’s own mind, what they’re hiding from themselves, what they think full or normal instrospection might be. If one of Kazuo Ishiguro’s characters declines to examine his thoughts, is the author likely to have a similar reticence? How can the two be distinguished?

When Mearsault’s inner life fails to materialize—when he fails to cry at his mother’s funeral or even to think of her except when he’s prompted, when he fails to realize people disapprove until he’s on trial—the book creates a puzzle: where, exactly, is his inner life? Are we seeing all of it? These are the things I would like to be able to explain about Mearsault:

He doesn’t say whether or not he thinks about what his actions, or his life, mean. But does he, in fact, have such thoughts?

Did Camus think Mearsault had thoughts? What signs might there be that Camus—meaning the implied author of the book, not the person who was often interviewed—pictured his character as something more than a perceiving and acting machine? And what sorts of thoughts would those have been?

Did Camus himself have an inner life? This last question might seem ridiculous, because we know a lot about Camus from his other writing. But I mean Camus the implied author. In other words: without looking up anything about Camus, does it seem the author of this book had an inner life?

All this is for the second half of this essay, after I do my best to argue that fictional characters with problems are better off unexplained.

One more bit of housekeeping. I keep pairing flat affect and lack of inner life. The two can be entirely separate. Detective fiction is full of emotional people with no apparent inner life (the colorful extras in any murder mystery, for example), as well as stone-cold killers who have fierce inner lives (even if they are mainly driven by revenge). I thought for quite a while that what I’m really attracted to is just the lack of parts of the fully reflective mind, but I have discovered there’s a mysterious connection between absences in thinking and absences in feeling, and a mind that knows very little of itself, or has forgotten much of itself, tends to be most interesting when those absences also subtract affect. I do not know why that is.

Flat affect as philosophy

In the last thirty years, popular reception of The Stranger—meaning on sites like Goodreads, Medium, and Substack—has taken the book more or less as the historical author Camus intended, as a forum on existentialism. Mearsault’s moral indifference can be seen as an effect of what Sartre understood as existentialism (the underlying indifference of the universe to human meaning, the “thrownness,” in Heidegger’s word, of our lives) or absurdism (the intolerable gap between the inbuilt human desire for sigificance and the meaninglessness of the universe). Mearsault, the “stranger,” could be any of these.

Here I agree with Nabokov on the subject of philosophical novels in general: they compel characters to proselytize in a way that is bound to be at odds with what we’re given as their own feelings. (This is a problem, I think, with The Stranger: the moments where Camus observes Mearsault’s discomfiture, his attempts to adjust himself to what people want, ring true in a different way than the passages, such as the last few pages, in which Mearsault is a spokesperson for absurdism.)

There is also a tradition of reading The Stranger that understands Mearsault as the product of his society. That makes sense of Camus’s historical moment, and links The Stranger to Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human (1948, six years after The Stranger), whose main character Yozo is exhausted by playing roles and falls into an “inhuman” alienation. The tradition of reading The Stranger as a book about the effects of social alienation is ongoing (for example by Germaine Brée, who edited a collection on The Stranger) and it opens the way to a reading of alienation as the result of colonial and postcolonial constructions of identity.

Flat affect as social alienation

Most scholarly reception has been directed at Camus’s blindness to the Algerian context. Critiques by Conor Cruise O’Brien, Edward Said, and others have stressed the invisibility of Mearsault’s Arab victim and Algeria in general. (See Alice Kaplan’s book for the reported truth about the Arab victim.)

Yet social context can’t help much with understanding flat affect because it’s also caused by the insulation provided by wealth. This is true especially in Edward St Aubyn’s books. Unchecked privilege is the cause of Patrick Bateman’s behavior in American Psycho, and it’s an interesting exercise to put Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation in the same category.

On other cases blank affect is the result of middle-class suburban life. This happens in some of Tao Lin’s work, and much of Anne Tyler’s. Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is a Japanese example.

The outstanding example of a writer who gives us cynical, disabused, pessimistic characters with low affect is Michel Houellebecq, starting with Whatever (Extension du domaine de la lutte, 1994). Readers who continue to be shocked or provoked by him are led to recognize their dependence on bourgeois culture, its emptiness, its superficiality and dishonesty.

The history of flat affect as as consequence of social alienation begins well before Camus. Its precedents are usually said to be Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener” (1853), Goncharov’s Oblomov (1859, the ultimate source for Moshfegh’s book), Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864), or Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” (1915). I’d like to suggest a more provocative starting point: Montaigne was also “alienated” from his society, surrounded by people who would not understand the point of his “essais,” always wanting to justify himself by reaching for ancient precedents, understanding his “alienation” as Stoic calm.

Flat affect and violence

In fiction and films, low affect heroes and heroines often turn out to be capable of astonishing violence. Mearsault’s blankness and his one-word responses are in line with any number of positive heroes in films, from Bogart to Daniel Craig, Jason Statham, Vin Diesel, and Keanu Reeves (John Wick)—all men who are taciturn, unemotional, deeply scarred, reluctant to act, and slow to anger, because they harbor unspeakable tragedies, devastating betrayals, and irreparable losses. (Why is this such a gender type? Why not an equivalent number of scarred, emotionless women who are also heroes?)

Brett Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero (1985) demonstrates that emotional numbness and affectless alienation do not need to result in violence, and it suggests that Ellis’s later American Psycho is an unnecessary dramatization of the condition sufficiently expressed in the earlier book. Violence is used in American Psycho to drive home the danger of affectlessness. There are many precedents aside from Camus, including J.G. Ballard’s Crash (1973), Bataille’s various transgressions and, farther back in history, Sade’s. But it’s also possible to imagine the connection between violence and low affect as an affectation, a popular-culture tic: it’s a relief, for some readers, from the unpleasant contemplation of emotionless narrators. Violence moralizes them, or at least provides some entertaining relief.

Flat affect and trauma

I am also uninterested in authors who use trauma to explain lack of affect. A model for emotional numbness understood in this way is Septimus Warren Smith in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), and I would add Freud’s ideas about the traumatized victims of the First World War in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920)—a book I prefer to read, with Harold Bloom, as fiction. An example from the Second World War could be Billy Pilgrim in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969).

The language of clinical psychology is helpful here. War-related post-traumatic stress disorders are one explanation for low affect in fictional characters. Trauma resulting in depersonalization is evident in books like Sylvia Plath’s Esther Greenwood in The Bell Jar (1963). Dissociative identity disorder is at work in Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996), whose central character is initially apathetic, and can’t cry or feel emotion—until he starts Fight Club. As in the case of violence, trauma may often be an unneeded element, an explanation, for the fact of flat affect.

Deferring explanations

I list these explanations to suggest they are not necessary. Flat affect and flattened emotions are forms of experience. They are most powerful when they are just set out, and not given trumped-up back stories.

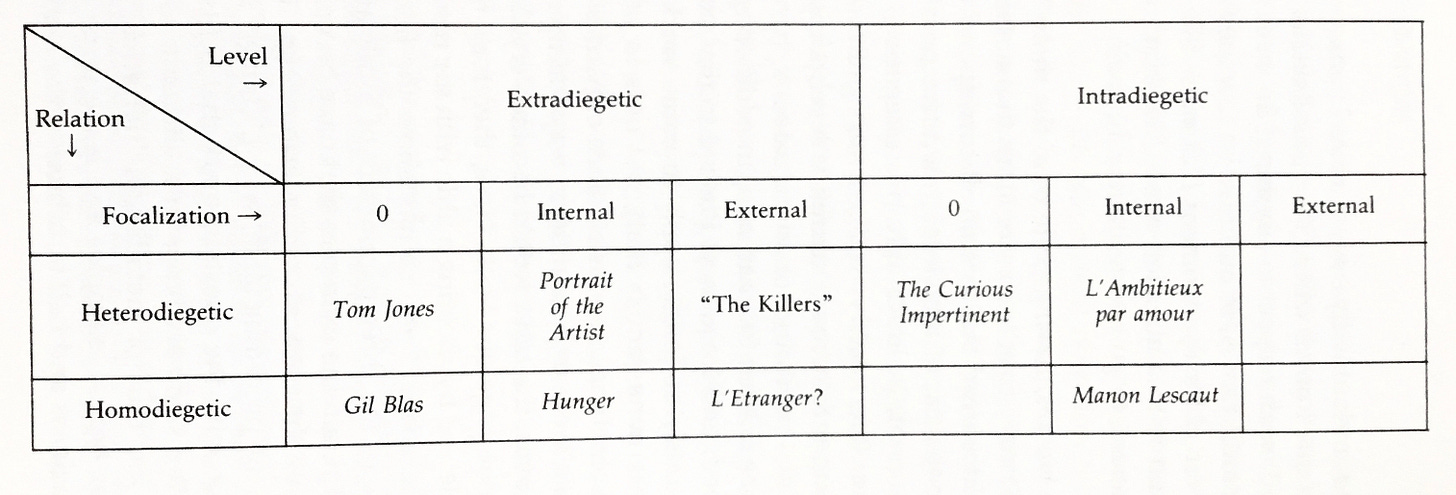

I think the best theory about how this might work is in Narrative Discourse Revisited, where Genette reviews his schema of what he calls “narrative situations.” There are three dimensions:2

The narrator’s position

Extradiagetic: the narrator exists outside the fictional world of the book

Intradiegetic: the narrator is in the fictional world

The narrator as a character

Heterodiegetic: the narrator isn’t a character in the story

Homodiegetic: the narrator is a character in the story

How much access readers are given to the character’s thoughts

Internal focalization: readers see and know only what the character knows

External focalization: readers know only what’s observable from the outside

Zero focalization: the narrator is omniscient, so the reader can know anything

Notice the question mark after L’Etranger. Genette quotes a study by Claude-Edmonde Magny:

The artful filtering Camus sets up consists of presenting a hero who says I reporting to us only what a third person could say about him.

Genette also notes Sartre was the first to say this, in his influential early essay “Explication de L’Etranger” (1943), “which reported and partly justified this anonymous witticism: ‘Kafka written by Hemingway.’” Genette comments that the “technical paradox” is “obviously that of an external focalization in the first person.”

These are fabulous conceptualizations, but notice what they do to Genette’s schema. The Stranger is homodiegetic because the character is in the story. The “external focalization of the first person”—a formula as logically precise as it is psychologically incomprehensible—means that the narrator exists outside the fictional world of the book (“L’Etranger?” is under the header “Extradiagetic.”) He has been expelled from his own story by excluding himself from internal focalization while keeping his first person voice.

The narrative mode of The Stranger, Genette says,

is “objective” on the “psychic” level, in the sense that the hero-narrator does not mention his thoughts (if any). It is not “objective” on the perceptual level, for we cannot say that Mearsault is seen “from the outside,” and… the external world and the other characters appear only insofar as… they enter his field of perception. [p. 123]

He comes to the clumsy formula that The Stranger exhibits “internal focalization with an almost total paralipsis of thoughts.” A paralipsis is a rhetorical figure in the speaker or writer draws our attention to something by not mentioning it. In Genette’s words, Sartre’s formula is that

we see everything through the window pane that is Mearsault’s consciousness, except that “it is so constructed as to be transparent to things and opaque to meanings.”

As Genette knows, none of these formulations is persuasive: Genette’s is awkward, and Sartre’s, as Genette points out, fails to say which side of the pane we’re on: are we inside, looking out at the world, or outside, looking in? The best way to think about it, Genette concludes, is to let the text have its mystery, and just say “Mearsault tells us what he does and describes what he perceives, but he does not say… whether he thinks about it” (p. 124).

Genette is mainly interested in the field of possibilities, and he thinks some combinations (like the ones at the far right column of the table) might be historically unlikely. There are still good open questions here for literary criticism and literary history. “Homodiegetic narrating with external focalization” is hard to maintain, and even in The Stranger there are moments when we hear Mearsault’s thoughts. A rigorous application would mean that an external observer would be “incapable not only of knowing the hero’s thoughts but also of taking on his perceptual field” (p. 125), so there’s a

Maybe The Stranger is strained because it’s an attempt to apply the perspective over the course of a book. After all, “homodiegetic narrating with external focalization” is used all the time in evanescent contexts, for instance in sentences like “I seemed like a jerk” (p. 126). Detective fiction (and, I would add, any number of wounded male heroes in film, from Humphrey Bogart to Vin Diesel and Jason Statham), typically presents heroes whose traumas have buried their emotions, but in Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler, this “behaviorist course… is somewhat strained”—there’s always the moment where the hero’s deepest feelings are revealed (p. 123).

This is, I think, the best attempt to theorize the representation of partly inaccessible minds, exactly because Genette is honest about his perplexity and the theory’s shortcomings. The problem remains unsolved in contemporary fiction, despite several generations of critics complaining about authors’ tendency to dip freely into their characters’ minds. How can writers manage persuasive acocunts of partly inaccesible minds, illegible motivations, lack of affect, and lack of inner life? How can readers trust writers to be depicting those states, rather than simply embodying the patterns of their own awareness?

Reasons for writing these essays

My interest is practical. I want to know how to control flat affect in fiction: how to tell a reader that it’s the character who won’t say “whether he thinks about it,” or the implied author. Who is saying, like Bartleby, I prefer not to think? Is it Bartleby, or is it Melville?

I would like to put this to work in Book 4 of the five-volume novel project called Five Strange Languages. In the first book (due out 2026/7), Samuel is a conventional character, with a range of emotions. He suffers a series of crises (Weak in Comparison to Dreams, A Short Introduction to Anneliese) and by Book 4 (due out 2027/8) he is close to his goal of removing feeling and attachment from his life.

My challenge in that fourth book, called Ghosts Are, is to present a character whose flat affect and lack of introspection are entirely his choice, but to make it clear that it’s Samuel who won’t say what he’s thinking: it’s not the author who has moved focalization outside of the character’s mind, but the character who has moved his own thoughts around so that some are not being shared.

Genette, Narrative Discourse Revisited, p. 123.

These have been refined and critiqued by many scholars. See for example Dorrit Cohn, Jan Alber, Brian Richardson, and Maria Mäkelä (as opposed to Maria Makela, a specialist on expressionism).

Bresson is an interesting case. In his films from the 1950s, the voice-over gives us access to the main character’s thoughts. Those are narratives based on the existence of a diary, and they seem to transpose a verbal content from written to oral form. We do not always see what they see, but even when the point of view could be described as objective, it is evaluated by those words.

From the mid-1960s onwards, Bresson pretty much throws the diary format out the window (Quatre nuits d’un rêveur is an exception, since the protagonist uses a recording device as a diary). The balance between first- and third-person that drove those earlier films is not possible anymore. What happens is that the editing and the overall structure end up taking the burden of psychological description, or, more precisely, suggestion.

Au hasard Balthazar is centered on a donkey, so any representation of the protagonist’s inner life can only happen through editing. Take, for instance, the scene at the zoo when Balthazar is put in front of other animals and Bresson recreates the Kuleshov experiment, the cinematic archetype of “projection of meaning on a flat, inexpressive surface”. Bresson, of course, wrote about this in his notes: he said that every element had to be neutralised so that meaning would emerge from the relationships established within the composition. It seems like a displacement from a substantial to a structural model.

In later films, the traditional soundtrack, usually a nonverbal expression of a character’s inner state, is also gone; fades and dissolves, which indicate the passage of time, give way to direct cuts. At the same time, those oblique shots and abrupt transitions are always directing our attention to the split seconds or subtle gestures when the lack of expression/justification matters the most. It’s an art of precise ambiguity, of managing, even inviting, projections within narrow limits. This is also why I think his main characters are not “black holes”, “without motivation”, or have “unusual mental states”.

Dashiell Hammett & Patricia Highsmith are, I think, still underrated masters of depsychologized characterization.

Hammett's protagonists rely on projecting confident competence to cover inner confusion: "Red Harvest" in first-person, & the third-person narrative voice of "The Glass Key" anxiously searching every character's eyes for meaning.

Highsmith's protagonists repeatedly find themselves acting in ways they can't explain to themselves, usually with tragic results. Untroubled impulse-surfing Tom Ripley is an exceptional success, as is the protagonist of "The Tremor of Forgery", an answer-novel to Camus.

As you suggest, there's often overlap between mysteriously-motivated central characters, mysteriously-motivated authors, & mysteriously-structured narratives, as with Beckett & Robbe-Grillet. Like you, I think, I'm drawn to all three tendencies.