Writers who won't tell us what's in their characters' minds, No. 4: Why unusual mental states may not need to be explained

This is a series of posts on a fascinating problem for contemporary fiction: What happens to fiction when a character’s mind is partly closed, either to the character or to the implied author? It’s not a problem to write about a character from the outside—to watch them, as we all watch one another, without having access to their mind. But it is a very difficult and interesting problem to “focalize” a character, in Gérard Genette’s term, so that we can read some of their thoughts, and yet to refuse others—to keep them off the page, or out of the character’s mind. To adopt and generalize Bartleby’s expression, what are the expressive possibilities of preferring not to say?

Here’s the series:

I’ve been thinking out loud, as it were, and all these posts are open to comments. I’d love to hear about other examples and theories.

This is a proposal, using Ingeborg Bachmann’s unfinished work as an example, that fictional characters’ mental states do not always benefit by being explained in terms of biography or history. Sometimes mental states are exactly that: conditions that require empathetic observation, not explanation.

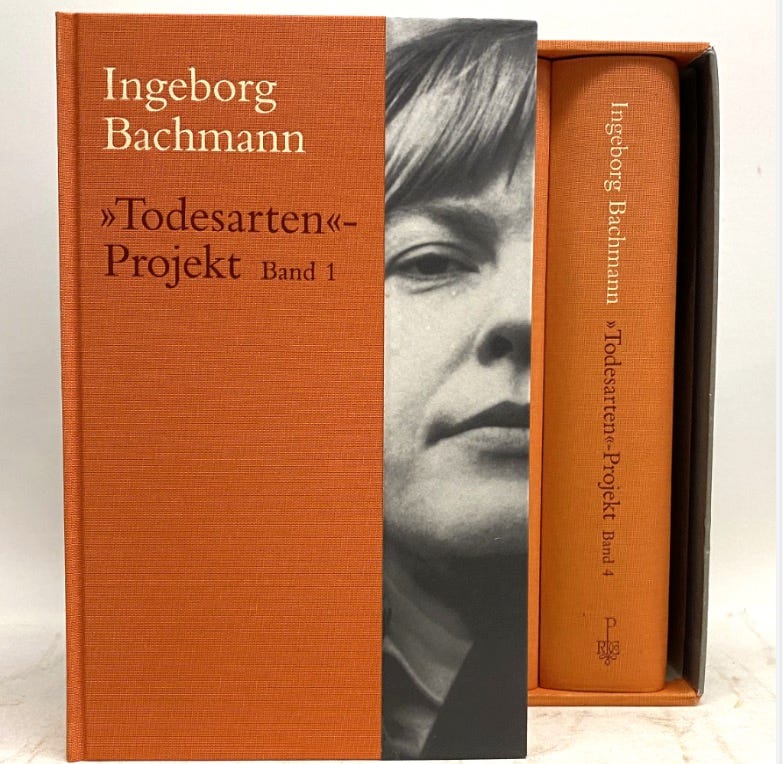

Ingeborg Bachmann's unfinished set of four novels Todesarten ("Arts of Death," or "Arts of Dying") has been seen as a crucial document in postwar feminism. There is no reason to contest that, but especially in light of Malina, the only one of the set that Bachmann finished (these two are incomplete, and the fourth is just scattered notes, available in the German edition), the identification of her work with feminism is only partly right and often misleading. In Malina there's a desperate struggle, on the part of the narrator and the author, to remain stable long enough to complete the book. (Please have a look at that argument here.)

If these two unfinished novels, written in 1965-66, before Malina, seem less troubled, it may be because they feel more attentive to, or obligated to, normative narrative forms. Even so, there are disturbing eruptions of severe dissociative thinking, especially in The Book of Franza. The translator, Peter Filkins, talks about Franza's "inability to mourn" for her own destroyed life, and even though that is a Freudian conception, it feels more contemporary than this novel, where psychoanalysis is no solace or explanation—in fact Franza has been destroyed by the psychoanalyst to whom she is married. She suffers sudden bursts—hernias, really, open wounds—of trauma. Her brother hopes that by taking her along to Egypt he can at least distract her from her suffering, but her mind has been mortally wounded by her husband. Her brother is helpless:

"She had not arrived at Luxor but instead at a point in her illness, not having traveled through the desert but through her illness. In the evening she collapsed. I have seen how I will die, she said." (p. 105)

Franza collapses, trembles, is physically sick, spends hours just sitting. It is clear from early on that she will not live, will fail to cure herself.

The Book of Franza, Requiem for Fanny Goldmann, and Malina are about women who are nominally alive but actually broken, incapable of reaching old age. Bachmann provides reasons—not justifications or explanations—for the ways the men effectively murder their wives. Franza's husband is an internationally famous analyst in Vienna, and he married her in order to make her into an experiment. She discovers papers in which he records how he is systematically destroying her. Fanny's second husband uses his relationship with her to advance his career, effectively stealing her soul by transplanting it into his own novel. Both women die later, when the men they love are no longer present. (Although "love" sounds wrong here: Franza and Fanny pathologically and misguidedly depend on men, and experience that as love.)

I'd rather Bachmann hadn't added the plot points about the mens' motivations (the psychoanalyst apparently advances his theories, and the novelist thinks he can save his career) because cruelty is endemic in life and in her work, and the sinister plots and revelatory documents seem at once contrived, ineffective as explanations, and false flags presenting universal sadism and violence as career choices.

It's harder to object to Bachmann's wider theme that Austrian minds were contorted into cruelty by guilt and anger over the war, and that Franza's destruction cannot be thought about apart from the damage caused by the war. There are references in The Book of Franza to the Nuremberg trials and to SS doctors who experimented on prisoners. But in the end, I don't think those are necessary either. Franza's death in a distant country, fifteen years after she married the analyst, is not so much explained by the violence of the Second World War as it is a picture of the kind of diseased lives that could just as much lead to another war. There might be a lesson here for some writers: the story of the violence that leads Franza and Fanny to destroy themselves is not ultimately a contribution to feminism or the history of postwar Austria, and the books might have been even stronger if those few signposts had been pulled up.