The Most Perfect Book Review Ever Written

Nabokov's one-page review of the English translation of Sartre's Nausea

Vladimir Nabokov's review of Nausea is the most perfect single page of criticism I know. It has a supernatural concision that finds room for a beautiful balance of topics and emphases. It begins with small points and progresses to an idea so large, so fundamental, that it could be the subject of a year-long seminar. I offer some remarks on it here, in place of the ten milionth review of the book itself.

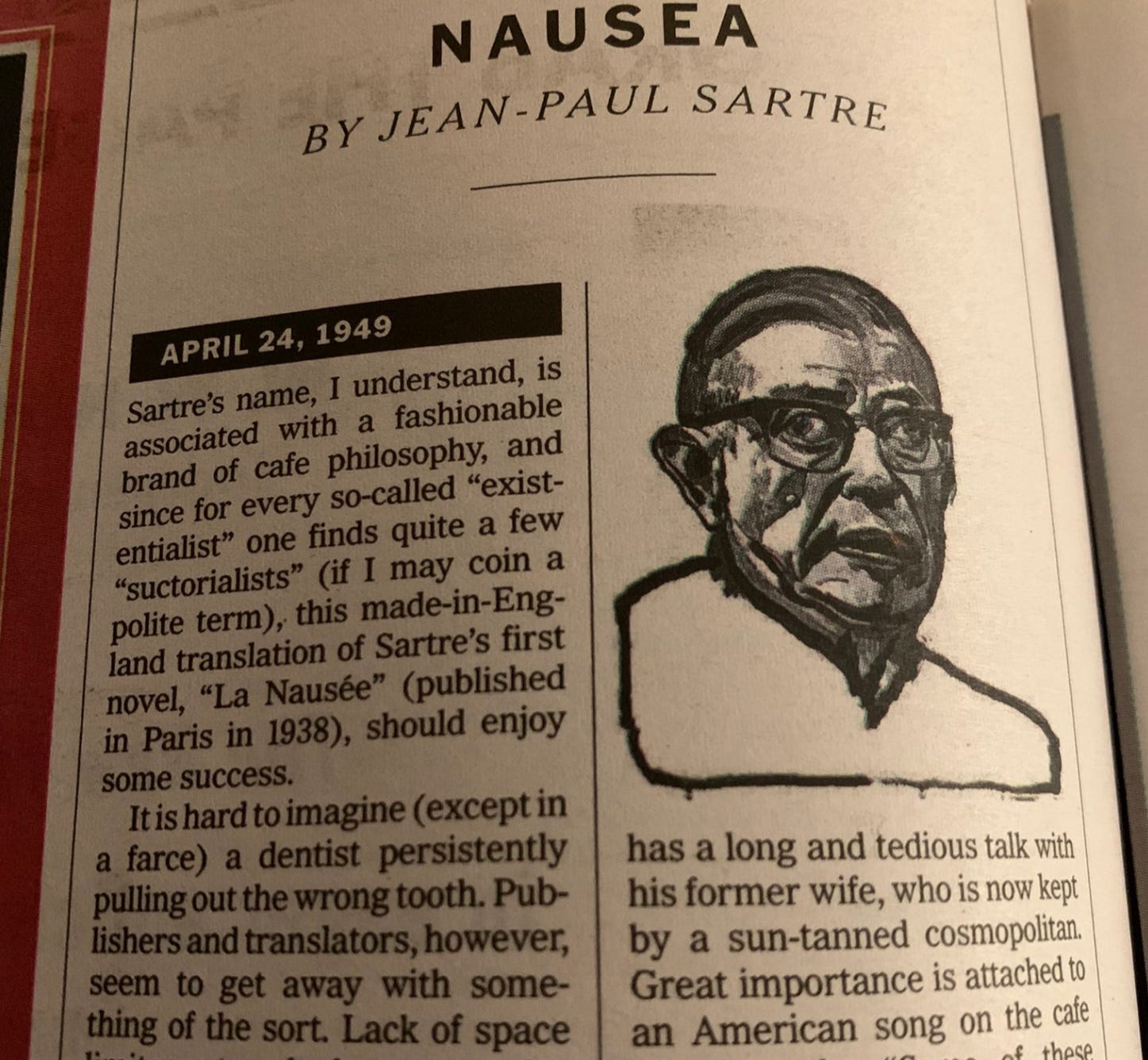

Nabokov's piece is so short I encourage you to read it first. It's here: tinyurl.com/sartrenabokov.

The opening paragraph is charming, snide, and condescending all at once: three admirable qualities for a review, because they promise the reader an interesting critic, as well as—or in place of!—an interesting author.

Then comes the critique of the translator of Sartre's novel. Nabokov was fluent in French, even though he said he was never influenced by his years in France one way or the other. (He declined to be wowed by Paris, as he knew he was supposed to be.) His ease with French is on impeccable display, and the three examples are perrectly chosen: they are funny—they're what contemporary reviewers so aggressively call "howlers," concisely establishing the translation he's reviewing is appalling.

Note there are only four more paragraphs in the review.

The first is a literary genealogy for Nausea, which is still read as a philosophical novel written by a philosopher—that is, a work whose place in the history of novels isn't always pertinent. In this brief paragraph Nabokov provides a sketch for a new style (a "really very loose type of writing"), traces it to Dostoyevsky ("at his worst," presumably the programmatic parts), and then traces Dostoeyevsky to a lesser-known progenitor, Eugène Sue (1804-57). It's infinitely suggestive and plausible, and fulfills the part of the critical task that requires history.

The next two paragraphs complete the plot summary Nabokov began in the first. Any account of the content of an artwork has to abbreviate, and given that necessity it's often best to select just one passage, part, or episode. Nabokov's choice is Sartre's fantasy of an American composer. It turns out Nabokov's description is all clichés (I count seven) and isn't even factual (the composer was Canadian).

It really helps, in criticism as in any writing, if the writer can put words together well. Nabokov was, on many scales, a brilliant writer, and the phrase "in an equivocal flash of clairvoyance" is amazing: it's intriguing (since we haven't yet seen the evidence) and, in retrospect, a crystalline verdict.

The final pargraph is five sentences. First: Nausea is an existentialist novel. Then comes a trenchant criticism of philosophic novels in general: their philosophy is "on a purely mental level," meaning it's detached from the feelings and experiences of the rest of the novel. But instead of saying that, as I've just done, Nabokov gives an example, making it immediately clear why it's not a good idea to superimpose the "purely mental level" of philosophy on a novel. In such a novel, the character, Roquentin in this case, is "hapless": invented from other parts of the writer's imagination, vulnerable to misuse by the autocratic novelist, who "inflicts" his philosophy on him. Notice that Nabokov isn't saying that Sartre's philosophy is an "idle and arbitrary fancy": things appear that way because Roquentin is a living creature with his own thoughts. That's why (in the second-to-last sentence) a reader won't be annoyed at Roquentin. But they might well be vexed at the author (the last sentence) because he wasn't capable of imagining a world in which the character and his ideas are a connected. It's a wonderful critique of the entire genre of philosophical novels.

So in one brief page, you have: a critique of materials (in this case, translation), a plot summary, fact-checking, a review of the pertinent history, a philosophic rumination, and an exceptionally strong and deliberately overstated judgment (the book wasn't worth translating). And almost a dozen memorable turns of phrase. A perfect work of criticism.

What a great review. Feels very lightly edited compared to NYT reviews today: they clearly let him say what he wanted to say.

I had a college professor once who made us write cogent one-pagers like this every week. Not one word more than a page and it had to make a point and prove it from the text. Made us smarter and sharper, for sure.